STROMBERG PLAIN TUBE CARBURETORS:

Introduction; What the Carburetor

Should Do; The Stromberg Plain Tube Carburetor Principle; Type "0" Series

of Vertical Carburetors; Type "0" Series of Horizontal

or Side Outlet Carburetors; Adjustments; Servicing and Maintenance;

Directions for Proper Installation, Settings, and Adjustments;

How to Locate Engine Troubles.

INTRODUCTION

The following pages contain an explanation of the principles employed

in the Stromberg carburetors, together with a brief description

of the different models.

They also describe the procedure by which the requirements of the

engine are ascertained and the carburetor setting co-ordinated

therewith.

Since in actual service the mixture requirements of the engine

are an all important consideration, ithas been considered advisable

to open the subject with a chapter describing the conditions existing

during the intake stroke and showing how the mixture requirements

of one engine may be different from those of another.

This information will be found particularly valuable in service

work, as it will give an understanding of deficiencies due to engine

faults which are often erroneously ascribed to the carburetor.

WHAT THE CARBURETOR SHOULD DO

Combustion Requirements; Vaporization; Mixture Proportions Needed

From Carburetor

The carburetcr furnishes the fuel charge, without which the engine

cannot operate; it also is the means by which the driver controls

the motion of the automobile.

No matter how carefully built the rest of the engine may be, the

car will be sluggish, if the carburetor does not furnish the proper

mixtures in obedience to each slight touch of the driver's foot

on the accelerator pedal.

The responsiveness of the engine and a large part of the pleasure

obtained from driving a car depend upon the carburetor.

There are other elements which enter into the operation of the

engine. The speed, load, temperature, manifold, and nature of the

fuel, each have an effect, and the best carburetor is the one which

best graduates the fuel feed, or mixture proportion, to suit these

different conditions.

In the early days of the automobile it was believed that one fixed

proportion of air to gasoline would give the best performance under

all conditions. It is now known that this is not true, and the

present success of the Stromberg carburetors is largely due to

their ability to give a properly proportioned mixture under different

conditions.

The following chapters explain how the mixture delivered by the

Stromberg carburetors is con-trolled, and why, and how it is varied

to meet these different engine conditions.

Combustion Requirements

Mixtures that can be burned: To burn gasoline or kerosene completely,

the fuel must be mixed with about fifteen times its weight, or

nine thousand times its volume of air.

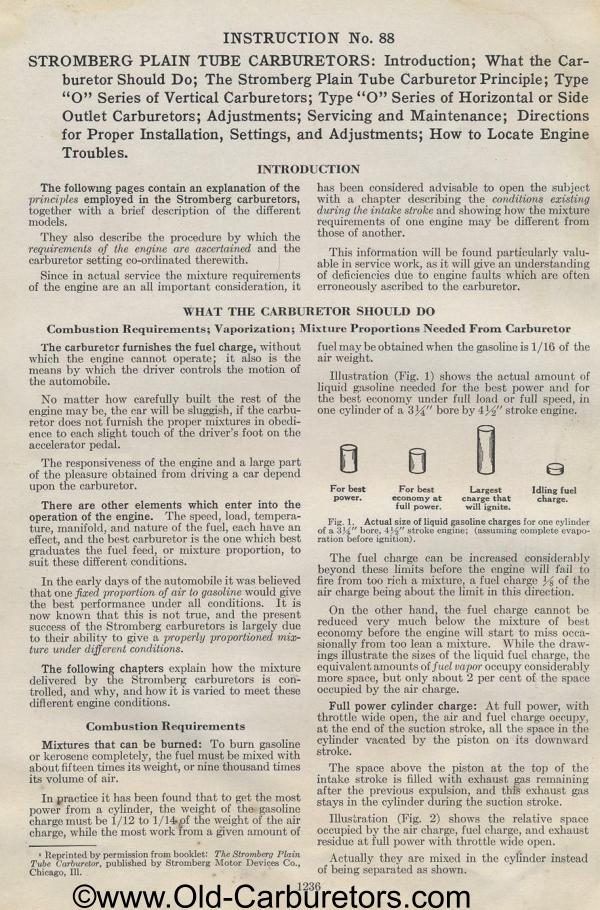

In practice it has been found that to get the most power from a

cylinder, the weight of the gasoline charge must be 1/12 to 1/14

pf the weight of the air charge, while the most work from a given

amount of fuel may be obtained when the gasoline is 1/16 of the air

weight.

Illustration (Fig. 1) shows the actual amount of liquid gasoline

needed for the best power and for the best economy under full load

or full speed, in one cylinder of a 3%" bore by 4 " stroke

engine.

For best For best Largest Idling fuel

power, economy at charge that charge.

full power. will ignite.

Fig. 1. Actual size of liquid gasoline charges for one cylinder

of a 3)i" bore, 4%" stroke engine; (assuming complete

evaporation before ignition).

The fuel charge can be increased considerably beyond these limits

before the engine will fail to fire from too rich a mixture, a

fuel charge of the air charge being about the limit in this direction.

On the other hand, the fuel charge cannot be reduced very much

below the mixture of best economy before the engine will start

to miss occasionally from too lean a mixture. While the drawings

illustrate the sizes of the liquid fuel charge, the equivalent

amounts of fuel vapor occupy considerably more space, but only

about 2 per cent of the space occupied by the air charge.

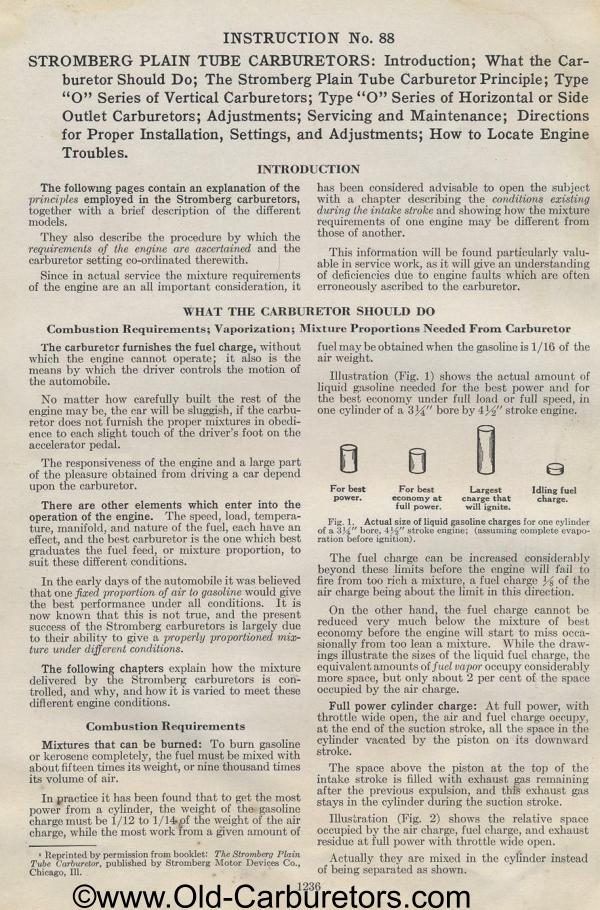

Full power cylinder charge: At full power, with throttle wide open,

the air and fuel charge occupy, at the end of the suction stroke,

all the space in the cylinder vacated by the piston on its downward

stroke.

The space above the piston at the top of the intake stroke is filled

with exhaust gas remaining after the previous expulsion, and this

exhaust gas stays in the cylinder during the suction stroke.

Illustration (Fig. 2) shows the relative space occupied by the

air charge, fuel charge, and exhaust residue at full power with

throttle wide open.

Actually they are mixed in the cylinder instead of being separated

as shown.

Previous page 1927

Supplement Home Next page

|