DYKE'S INSTRUCTION No. 88 (Supplement)

Fig. 6. Large view shows action of "over-lap" valve timing

in permitting exhaust gas to flow across cylinder into in-take

manifold, when intake and exhaust valves are open at same time,

at beginning of intake stroke: ENGINE under L I G H T LOAD, NEARLY

CLOSED THROTTLE.

Small view at right shows re

sulting proportions of air, gasoline vapor, and exhaust at beginning

of compression. Note large quantity of exhaust.

With this valve timing, it is usually more difficult to get smooth

engine operation at idling and low speed.

It is particularly necessary that the valve tappet clearance be

kept uniform, as varying degrees of overlap in different cylinders

will give them different strengths of charge, making irregular

firing which cannot be cured by any carburetor adjustment.

Misfiring on the comeback or when coasting: The least amount of

air in cylinder, and the most unfavorable conditions for firing

are obtained when the engine is turning over at high speed with

the throttle closed to the idling position, when each cylinder

has time to receive only a very small air and fuel charge.

This condition is reached when the car is coasting down a steep

hill with gears in mesh and the throttle fully closed. Such a condition

also exists temporarily when the engine is raced from idle up to

high speed and the throttle quickly closed.

Owing to the small amount of air and very high percentage of exhaust

dilution, the burning in the cylinder is very slow, while on account

of the high engine speed, there is very little time for each combustion

to be completed; so that with small defects such as intake leaks,

exhaust leaks or weak ignition, the engine is very apt to miss

or fire in the muffler under conditions just described. The tendency

to misfire is less with full advanced spark.

Vaporization

Vaporization of fuel necessary: It should be understood that gasoline

in liquid form or drops will not burn efficiently in an engine.

In nearly all forms of burning or combustion with which we are

acquainted, complete burning must be preceded by vaporization.

Under the flame of a candle or kerosene lamp, there is a heated

region filled by vapor of the tallow, paraffine or kerosene, the

wick serving as a means for graduating the supply and controlling

the formation of this vapor.

Wood and coal commonly burn by the process of distillation or evaporation

into inflammable gas before burning, and so on; and if we attempt

to burn any of these common inflammable substances, including gasoline

itself, by heating them highly when they are not intimately mixed

with air, we obtain smoke, soot and carbon or coke deposit.

Parts of the fuel charge that can be used. In the automobile engine,

with the short time allowed for explosion, only vaporized fuel

can burn and it is, therefore, necessary in any work with mixture

pro-portion that the extent. of fuel vaporization be taken into

account.

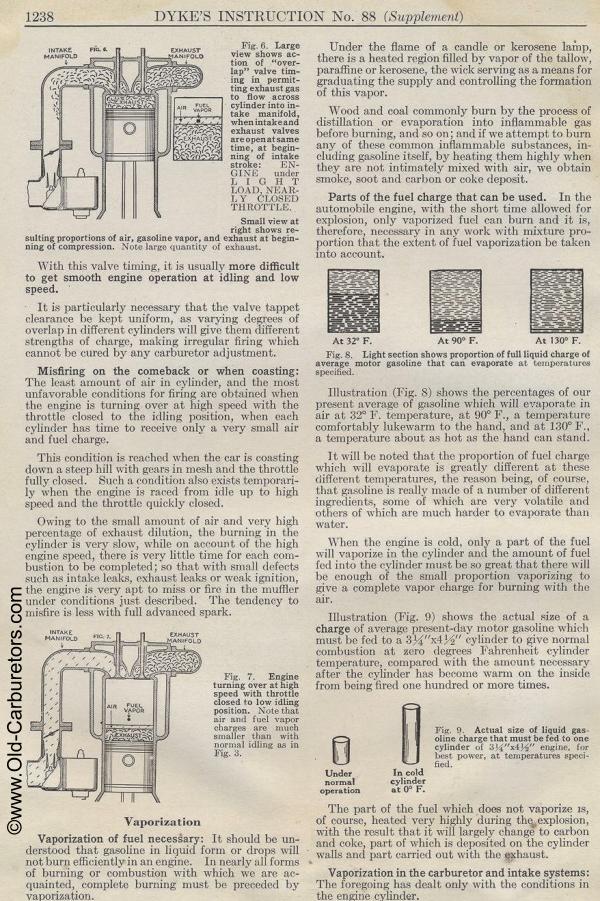

At 32° F. At 90° F. At 130° F.

Fig. 8. Light section shows proportion of full liquid charge of

average motor gasoline that can evaporate at temperatures specified.

Illustration (Fig. 8) shows the percentages of our present average

of gasoline which will evaporate in air at 32° F. temperature,

at 90° F., a temperature comfortably lukewarm to the hand,

and at 130° F., a temperature about as hot as the hand can

stand.

It will be noted that the proportion of fuel charge which will

evaporate is greatly different at these different temperatures,

the reason being, of course, that gasoline is really made of a

number of different ingredients, some of which are very volatile

and others of which are much harder to evaporate than water.

When the engine is cold, only a part of the fuel will vaporize

in the cylinder and the amount of fuel fed into the cylinder must

be so great that there will be enough of the small proportion vaporizing

to give a complete vapor charge for burning with the air.

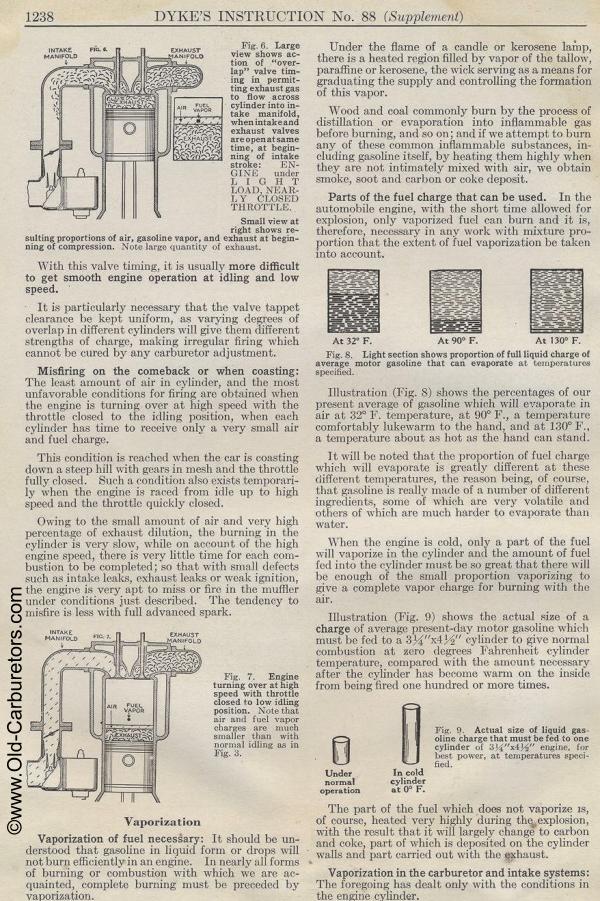

Illustration (Fig. 9) shows the actual size of a charge of average

present-day motor gasoline which must be fed to a 3%"x4%" cylinder

to give normal combustion at zero degrees Fahrenheit cylinder temperature,

compared with the amount necessary after the cylinder has become

warm on the inside from being fired one hundred or more times.

Fig. 9. Actual size of liquid gasoline charge that must be fed

to one cylinder of 3engine, for best power, at temperatures specified.

Under normal operation

The part of the fuel which does not vaporize Is, of course, heated

very highly during the explosion, with the result that it will

largely change to carbon and coke, part of which is deposited on

the cylinder walls and part carried out with the exhaust.

Vaporization in the carburetor and intake systems: The foregoing

has dealt only with the conditions in the engine cylinder.

Fig. 7. Engine turning over at high speed with throttle closed

to low idling position. Note that air and fuel vapor charges are

much smaller than with normal idling as in Fig. 3.

in cold cylinder at 0° F.

Previous page 1927

Supplement Home Next page

|